1950's and Chicago

1950's Cost of Living Stats

The Chicago Ward System

Chicago has been divided into municipal legislative districts called wards since its first municipal charter in 1837, which created six wards. Except for the single alderman allotted to wards Three and Five until 1839, each ward elected two members of the Common Council. The number of wards increased repeatedly in the nineteenth century to accommodate growth in population and territory, eventually stabilizing at 35 wards after the major annexations of 1889. In 1923, the current system was adopted, with one alderman representing each of 50 wards. State law requires that ward boundaries be redrawn after each federal census to ensure roughly equal representation by population size. In the 1970s and 1980s there were five court-ordered partial redistrictings to redress the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities.

Each district is represented by an alderman who is elected by their constituency to serve a four year term. In addition to representing the interests of their ward residents, together the fifty aldermen comprise the Chicago City Council, which serves as the legislative branch of government of the City of Chicago.

The legislative powers of the City Council are granted by the state legislature and by home rule provisions of the Illinois constitution. Within specified limits, the City Council has the general authority to exercise any power and perform any function pertaining to its government and affairs including, but not limited to, the power to regulate for the protection of the public health, safety, morals and welfare; to license; to tax; and to incur debt.

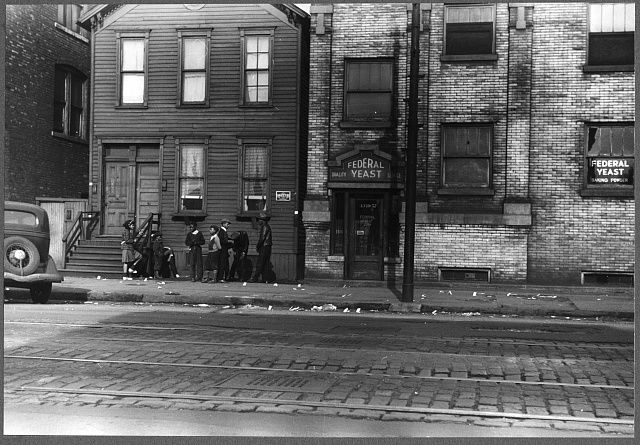

Employment Landscape in Chicago

- European immigration nearly halted after World War I, immigration from Europe was - Factories opened doors to Black workers due to the labor need.

- For Black women, the doors were barely opened, but domestic work in Chicago offered higher wages and more personal independence than in the south.

- Chicago workers labored in industries including meatpacking, clothing production, iron and steel, the manufacturing of foundry, machine and agricultural implements, beer and liquor processing, furniture manufacture, and printing.

- White industrial workers were supported by a community network - they lived near their jobs, within neighborhood that offered institutions like saloons with offers of fellowship.

- Racial segregation kept the relatively few Black factory workers (pre-1916) in remote parts of the city, forcing them to search for daily transportation to and from work. This also blocked vessels of social interaction that could have reduced racial barriers.

- Until 1916, Black factory workers were very few and those that worked in the factories found jobs on the killing floors of the stockyards or in the steel mills.

- Black men mostly worked as unskilled laborers, restaurant waiters, Pullman Porters, bootblacks and hotel redcaps while Black women filled the laundry trades and other forms of domestic service.

- Black employees of hotels, restaurants and the railroads often found themselves employed in places which would not service their families as customers.

- To help gain the sense of fellowship white workers experienced, the Pullman Porters established one such organization titled the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids, the First African-American labor union chartered by the American Federation of Labor.

- When supplemented with tips the porter and maid jobs paid better than many other jobs offered to African Americans.

Unemployment, Barriers to Employment, and other Statistics

- Consistently, the unemployment rate for Black individuals was twice that of White individuals (9.9% versus 5% in 1954) (https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2013/08/21/through-good-times-and-bad-black-unemployment-is-consistently-double-that-of-whites/)

- Throughout the 1950's, African Americans had more difficulty in obtaining work than their White counterparts, despite African Americans making up a larger part of the labor force. This suggests that these workers were often the last hired, the first fired, in shift or gig work, and that more members of the household would work at any given time. (A somewhat outdated in language but accurate in stats study from the Census Bureau chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1953/article/pdf/employment-and-income-of-negro-workers-1940-52.pdf)

$3,004

$1,246

Median Income for Full-Time Service Workers, Male and Female, in 1955

6.8%

Percentage of practicing physicians in the 1950's that were women.

1.7%

Percentage of female practicing physicians that were Black women in the 1950's

Post Great Migration Housing

MIGRATION PATTERNS

-Although less well known than The Great Migration of 1910-1930, the period of 1940-1960 actually saw more African Americans arrive in the city due to the availability of industrial jobs during World War II and the collapse of the Southern share-cropping system.

- Approximately 60,000 African Americans had moved from the South to Chicago during 1940-44 in search of jobs.

- African Americans were primarily limited to an area of Chicago known as the “Black Belt,” which was located between 12th and 79th streets and Wentworth and Cottage Grove Avenues.

- As more and more migrants arrived, adequate housing was scarce, overcrowded, and rents skyrocketed.

- In an effort to keep African Americans out of their neighborhoods (during the Great Migration and this secondary migration), Whites within a residential block formed “restrictive covenants” - legally binding contracts that specified a house’s owner could not rent or sell to Black people. Such covenants, by restricting African Americans to the Black Belt, increased overcrowding.

BLACK BELT CONDITIONS

- Housing demands far exceeded supply. Families would often live in one apartment, landlords would divide apartments into tiny units called “kitchenettes” and charge exorbitant rents. These apartments often had no bathrooms, with all the occupants of a floor having to share a single hall unit.

- Buildings sometimes lacked such basic amenities, such as proper heating. Residents used kerosene lamps instead, and their improvised stoves often overheated and caused fires. The partitions used to divide the apartments were flammable as well, adding to the hazardous conditions. Approximately 751 fires occurred in one year in the Black Belt, many of them fatal.

- Despite building codes, landlords were rarely penalized for owning slum housing and the few landlords who were fined found it was far more profitable to pay the usually small fine than to maintain their buildings.

- Neglect and indifference from city officials led to poor sanitation. Tuberculosis and other diseases spread; the infant mortality and overall death rates were higher in the Black Belt than in the rest of Chicago.

WHITE FLIGHT AND HOUSING SHIFT

- A predominantly White housing boom on the fringes of the city and in the suburbs meant more available housing in the city.

- After World War II, there was an outward migration from the Black Belt into surrounding neighborhoods due to this housing shift and a larger Black middle class.

- Though some families found the new housing situation they were seeking, others found a new but familiar cycle of poverty.

- Practices known as “block busting,” in which speculators tried to convince working-class Whites that their neighborhoods were going to deteriorate owing to an influx of African Americans, took advantage of White fears. Thus, when the speculators offered cash for a house, the White owners often accepted less than the house’s actual value on the assumption that their houses would be worth even less later.

- Speculators also took advantage of "redlining", where banks would draw a red line around an “undesirable” neighborhood and deny mortgages to the new African American residents. As a result, although African Americans fought housing discrimination by protesting and filing lawsuits, the first African American families seeking to move into these areas would have no choice but to work with the speculators on extremely disadvantageous terms; low down payment, but massive mortgages.

- Since the African American families would also have to sign an installment contract that left the title to the house in the speculator’s possession, a family could be evicted for the smallest violation of the housing agreement.

- African American families resorted to the practice of taking in large numbers of boarders. This recreated the condition of too many occupants in too little space.

- Additionally, Black neighborhoods did not receive the same quality of city services, recreating the former housing cycle.

RACE AND NEIGHBORS

- Riots by White mobs were not uncommon. Most Chicagoans, however, had no idea of the situation’s volatility. For much of the 1940s, the major newspapers, at the request of the Chicago Commission on Human Relations, would simply not report the occurrence of these riots.

- The White families who lived along the border of the “Black Belt,” and could not afford to move formed neighborhood associations to let African Americans know that they were not welcome.

- Sometimes, the first African American family to move into a White area would require police escorts in order to move around the neighborhood. They suffered constant verbal abuse and the threat of physical violence. Their property was damaged by hurled bricks and explosives were thrown through their windows.